Why Did Dr Dre Dressed Like a Woman

Dr. Dre's Secret (Sequined) History

In 1983 a teenaged Andre Young ventured into a Hollywood punk rock club and West Coast hip-hop changed forever

Aficionados of West Coast hip-hop like to think that our geographical brand is on every piece of rap product consumed between Atlanta and Sydney. Yet the essence of hip-hop culture in 1982 Los Angeles, north of Pico Boulevard — one line of division in a uniquely divided town — boiled down to just the following:

- Graffiti and breakdancers on Venice Beach.

- The turntable stylings of DJ Ron Miller, aka The Caucasian for All Occasions.

- Age of Consent, three openly gay, non-ironic rappers. ("You might say, What's this shit? / Rappin' white fags? It just don't fit") Two men, one woman.

- Hit East Coast singles blasting out of boomboxes.

Three years after The Sugarhill Gang's "Rapper's Delight" and Kurtis Blow's "Christmas Rappin'," Michael Jackson and blandly competent rock acts like Asia ruled. The hip crowd blasted Prince from their Alpine stereos; genuine new wave was only a rumor for most. Even Captain Rapp's homegrown "Bad Times (I Just Can't Stand it)"—an unremarkable echo of Run-DMC's "Hard Times"—had yet to hit.

The real action was in Compton, south of Pico's cultural capital, a town your average Hollywood music exec could not find on a map despite being less than 20 miles from Sunset Boulevard.

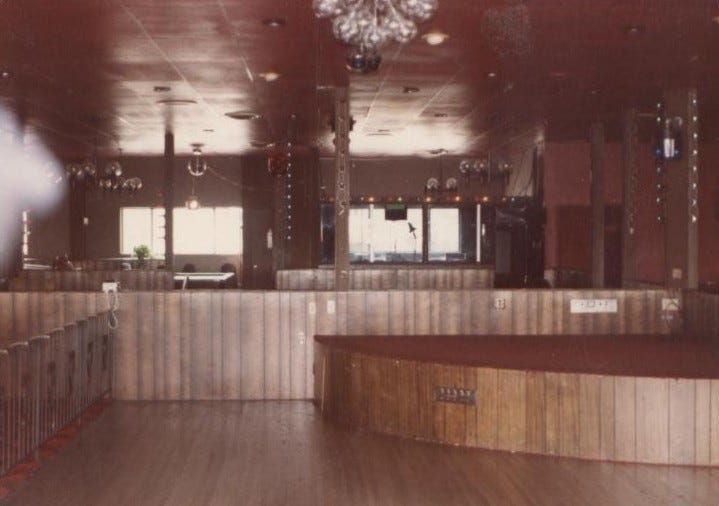

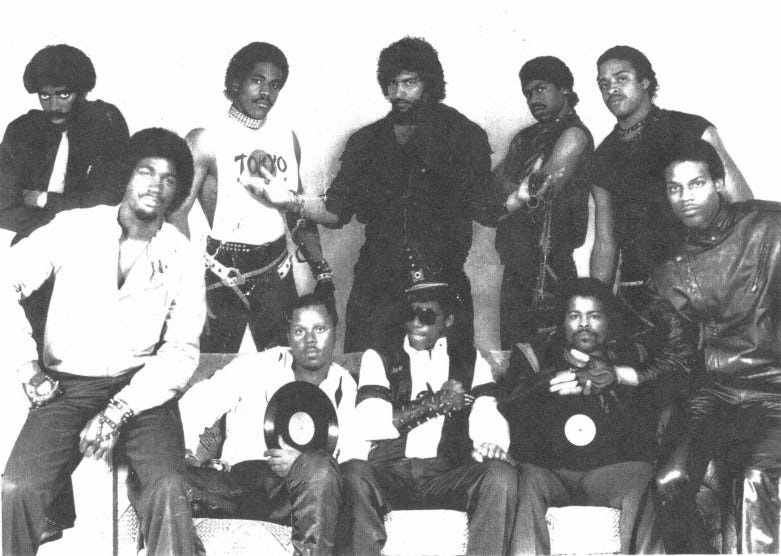

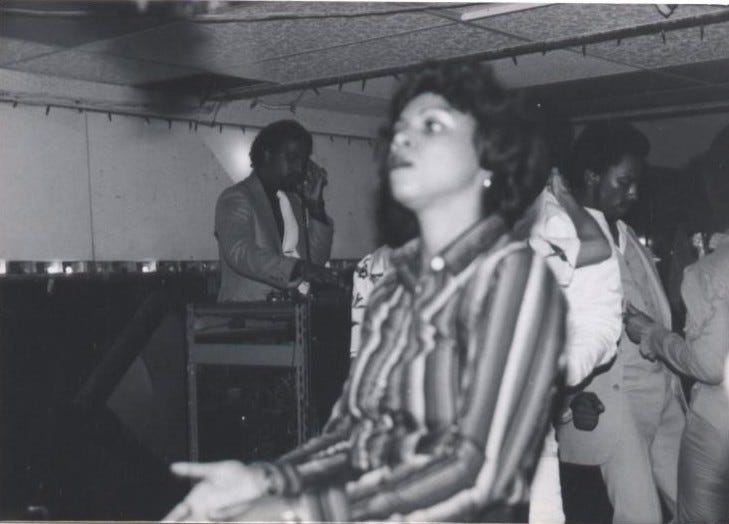

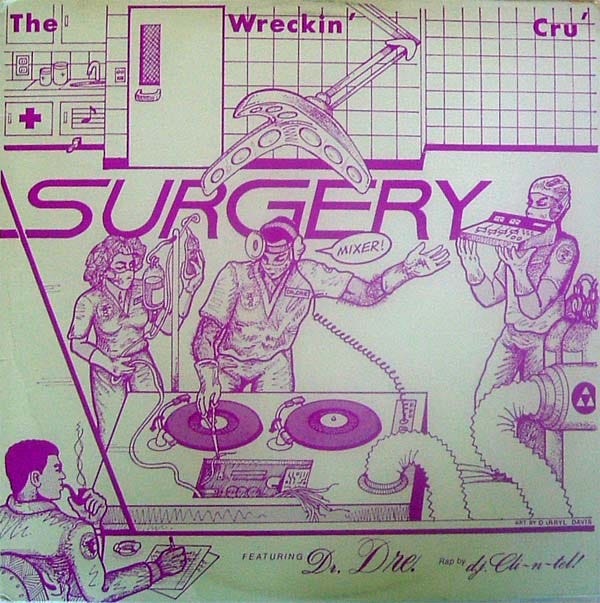

At the seminal nightspot Eve's After Dark, promoter and DJ Lonzo Williams was developing a kind of rap music that owed as much to funk as hip-hop. His group, The World Class Wreckin' Cru, featured future N.W.A member DJ Yella and a utility player of a teen named Dr. Dre. Problem was, South Central's scene was DJ-driven, and the record labels up in Hollywood, unable to imagine how they might monetize the movement, would not have known what to do with the doings at Eve's, in the unlikely event they found the Compton club on that aforementioned map.

At 1982's end, while hip-hop in L.A. beyond the Black part of town may only have been a curiosity, the culture was meandering toward a big qualitative leap. And neither the traditional record industry nor Tinseltown's recognized community of dance music DJs were going to have much to do with it.

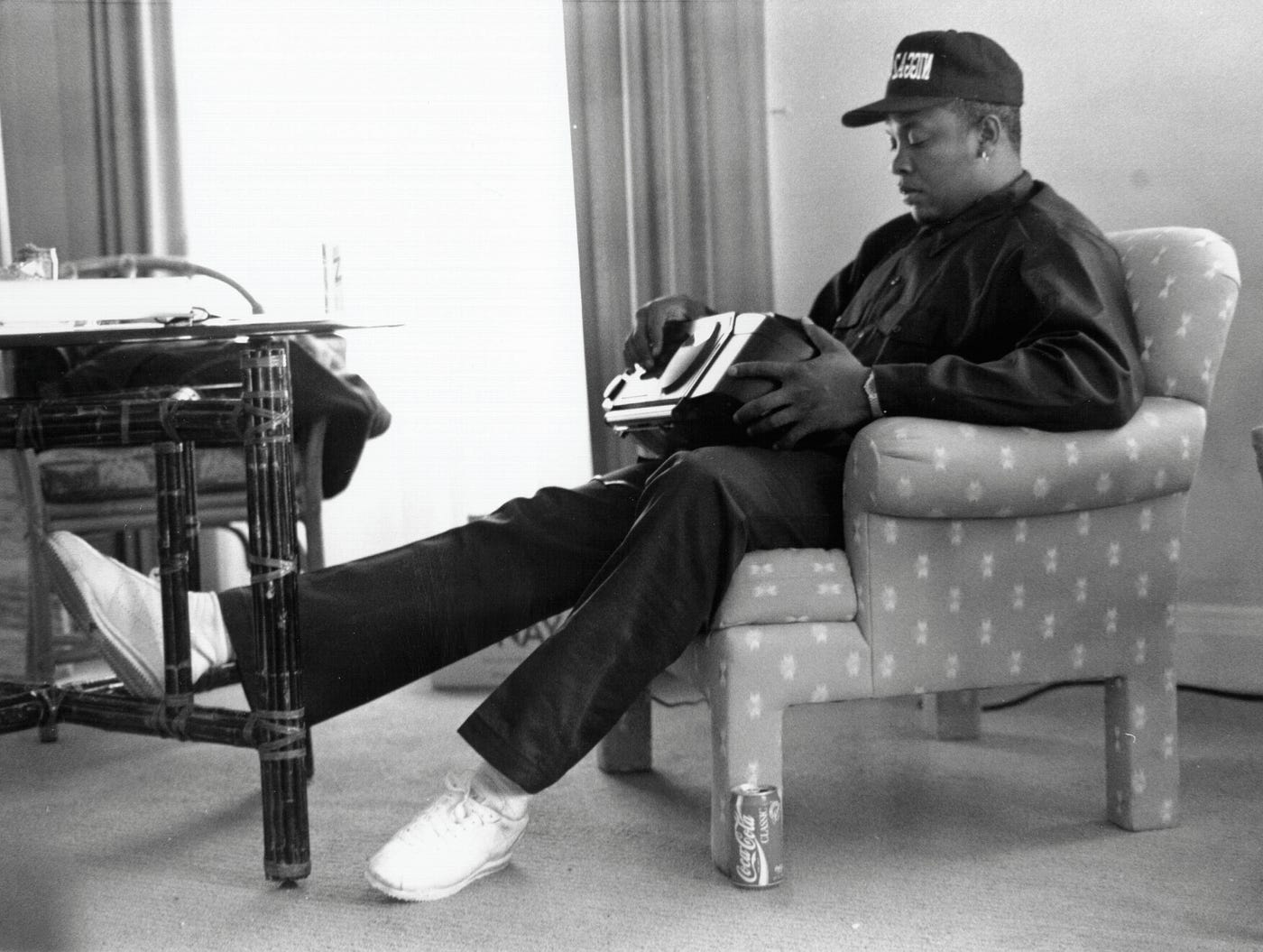

He's not an actual doctor, but Andre Young is arguably the architect of contemporary rap music. I have written a lot about him, including a problematic joint that coincided with Dre suing my co-author — his former best friend — upon our book's publication, and another that MTV Books just happened to cancel when I turned in a draft full of difficult details about how things went down at Death Row.

Based on all I've come to surmise about Dr. Dre, an adventure beyond the confines of Compton in February of 1983 had an indelible impact on him and — by extension — hip-hop culture as we've come to know it. Maybe not as important as the day Eric "Eazy-E" Wright picked up one of Dre's mixtapes at Compton's Roadium swap meet and told the booth's owner to put Dre in touch, put pretty damn close.

Here's how I came to to know about that weekend:

In early 2008, the late rock historian and promoter Brendan Mullen sent me a note about meeting Lonzo and Andre at a festival Mullen created in 1983. The Scotland native had breathlessly cornered me a few weeks earlier, just after I stepped down from a panel discussion at Barnsdall Art Center. Brendan Mullen told me I had a story no one had told.

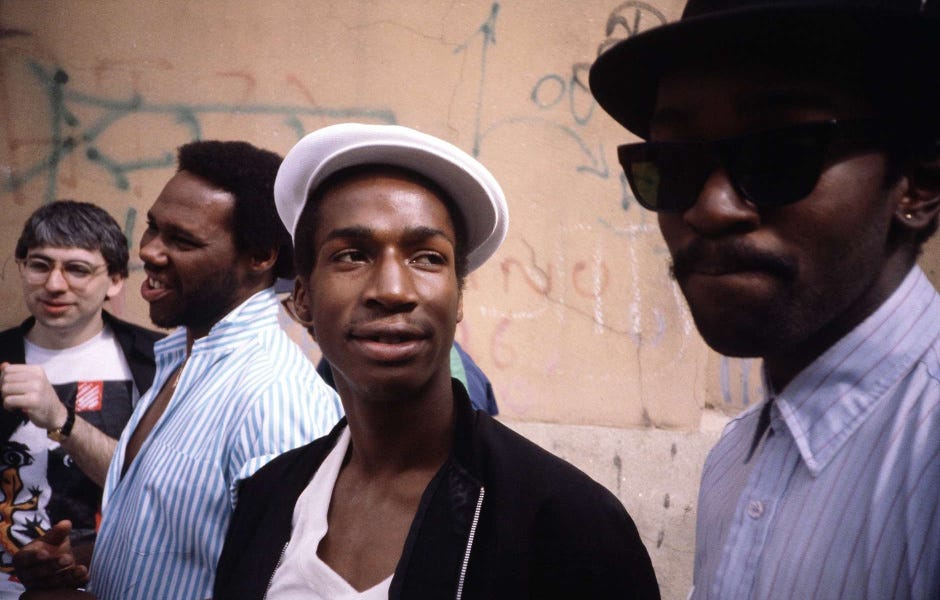

In his email, Mullen wrote that the Club Lingerie festival was "the first full-spectrum hip-hop event outside of New York, according to one key participant, DJ Afrika Islam, Son of Bambaataa, icon of the Zulu Nation b-boy tribe that Bam sent as his West Coast emissary."

(Islam was contacted for this story, but did not respond to the interview request.)

As early as 1981, Los Angeles nightclubs outside of South-Central were trying to figure out the hip-hop thing. Rodger Clayton's Uncle Jamm's Army had the party scene popular with working class people of color locked down since 1978. The broader world experiencing Los Angeles via media could see local hip-hop culture represented in TV commercials, via Venice breakdancers and the occasional graffiti throw up. There was, however, no L.A. County corollary to Bronx artists having taken the new goods downtown. And industry standard MC'ing, such as it was, could hardly be found in a Los Angeles live setting.

"We used to laugh at Ice-T when he was on the mic, he was so lame. But he got better," recalls Europa Macmillan, the rare female DJ in early 80s Hollywood clubs. Black hipsters on the late-night tip too were a rarity — both as performers and fans. Macmillan does recall Larry Fishburne, young members of a developing young band called Fishbone, and, eventually, Jean-Michel Basquiat making the scene.

Hip-hop was a bird of another variety.

"Sad to say that the French would have taken to it before we were able to in Los Angeles," Mullen wrote, referencing November 1982's "New York City Rap Tour," when Celluloid Records took Grandmaster D.St and Grandmaster Flash, as well as breakers and rapping graffiti artist Futura 2000 (The Escapades Of Futura 200 0), to France, "though it did take me a long time from mid-'82 to finally convince the club's owners to go for it."

Club Lingerie, on Sunset Blvd. between Highland and Vine, was a hub of the town's alternative music scene. This was when Los Angeles' rockers were playing sets on a qualitative par with anything coming out of New York or London, punk and new wave's acknowledged origin cities. Black Flag, X, Los Lobos, and my personal favorite, The Minutemen were just a few of the seminal L.A. artists making important noise. As Mullen explained, the next logical progression for a scene steeped in all manner of diversity, were stabs at hip-hop.

As mainstream as the music can seem now, one can forget it was generally taken as an affront to music well into its second decade. Mullen, who had a Saturday night DJ set before he began promoting live music at the club, began slipping a deliciously dated "Rapper's Delight" into his Saturday night set in 1981. Sure he dug the tune, but dude spun it equally because punk rock chicks would dance to it.

Five years earlier, Mullen founded the legendary Hollywood punk club The Masque, where many rockers first saw X, the Go-Go's and The Germs, among others. He was now at the height of his powers a spotter of talent and trends . Nineteen-eighty-three was also the year that neophyte artists Anthony Kiedis and Flea walked into Club Lingerie and found themselves on the way to a career. Jane's Addiction and other future stars were on the Peppers' heels.

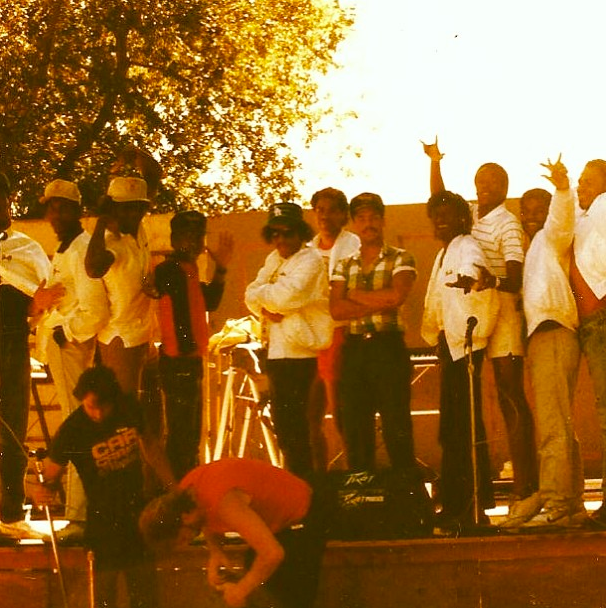

Forever on the lookout for the fresh, Mullen recommended that the nightclub's owners, Dave Kelsey and Kurt Fisher, spring for the costs of "bringing out a posse of kids straight off the street in the South Bronx, most of 'em loosely associated with the Zulu Nation as confirmed b-boys." The two-day event was christened "The South Bronx Invasion Goes West." Album cover artist Mike Doud (Breakfast in America, A Golden Shower of Hits, Houses of the Holy) did the fliers.

Mullen told me that Celluloid's Alex and Bernard "Change the Beat" Zekri, along with "dopefiend French artist" Alex Jourdanov pitched in to help organize. On the heels of the label's French tour, they were prepared to fly enough of its hip-hop talent—Dondi, Futura, Fab 5 & the turntablist formerly known as D.St—into LAX and fulfill its two-day commitment. Club Lingerie footed transport, lodging and per diem, according to Mullen.

"The advance buzz on the Lingerie show in the LA Weekly, the LA Reader, BAM music zine, and the LA Times was huge," he wrote. "Not just MCs, jokers or otherwise, but mind-blowing DJs, b-boy breakers and graffiti artists" and their promise produced an air of anticipation. Not all of it was favorable, according to Macmillan, who spun Lingerie that weekend.

"Everyone was really freaked out," Macmillan told me, "like, 'Oh my god, they're from the South Bronx! Are they going to wreck the turntables? Are they going to graffiti up the club?'" She said her only mild annoyance resulted from Futura 2000 taking forever to spray paint his name onto a big stage backdrop and from the one visiting crew member humping her derriere while she bent over the turntables in an extremely short skirt.

Macmillan recalled that most of the cast from Charlie Ahearn's film Wildstyle performed over the weekend. It is unclear whether the Cold Crush Brothers or Busy Bee rocked the Club Lingerie stage. Saturday's show was poorly attended, but Sunday's day-long event drew many more people. Grandmaster Flash spun and Fab 5 Freddy, whom Mullen said told him the trip marked his first time on a plane, rocked the mic.

Unaware of the goings-on at Eve's After Dark, the Hollywood set was amazed, especially, by the turntable techniques Flash and company had imported. Macmillan said she hadn't previously seen DJs cover their vinyl labels so as to keep secret what they spun.

In his 2008 email, Mullen claimed that one paying customer in particular had his mind blown:

An astounded Lonzo Williams, noted promoter at the club Eve After Dark which was regarded as the hip, young black spot of the time introduced himself to me and followed me around the club demanding to know how on earth I'd come up with these guys and the concept. He just didn't believe me when I kept telling him there was NO AGENT, no one put the package together. He kept relentlessly bugging me over what agent I'd booked the package with. "C'mon, man.." he said.."don't do this to me.. it was (talent manager) Norby Walters, right? Who did you talk to? What agency? Out here? New York? Where? How? C'mon, man.. don't you be holdin' out on me…"

He looked like he was experiencing something from another planet as he took in the second day of the festival. I remember him commenting it would never catch on with black culture in any big way because it was so raw; too loud, too raucous, too obnoxious! The exact same things the industry had said about punk rock in the late 1970s.

"That just don't sound like me," Williams told me upon hearing Mullen's description over the phone.

This is just one of many discrepancies between the two over the historian's account. I'm a major fan of Brendan Mullen. However, the points where he and Williams disagree about what went down at Club Lingerie on the first February weekend of 1983 are more than worth noting.

Williams copped to remembering little-to-nothing of "The South Bronx Invasion" specifics.

"It might be the first one he ever experienced," said Williams, who founded the ground-breaking World Class Wreckin' Cru and nurtured a then-teenaged Andre Young. He claims not to know one name of an MC who performed at Club Lingerie. "We were doing Kurtis Blow and Run-DMC shows for years," he said.

Another point of disagreement merits particular attention. According to Mullen, "Standing next to [Williams], wordlessly, the entire time was a skinny, confused-looking 17-year-old with a distinctive face who I recognized later on from record sleeve pictures of the World Class Wreckin' Cru, all framped up in ridiculous rhinestone pimp jumpsuits. The same kid who also showed up at N.W.A's first disastrous gig opening for Salt n' Pepa, Whodini and Whistle at the Hollywood Palladium a few years later," Mullen recalled. "To this day, I'll never know how he managed to sneak past our door staff who were primed to be inflexibly strict on 21+ picture IDs; he must've claimed he was one of the performing rappers, or more than likely, Lonzo blagged his way in for both of 'em."

Williams recalls the festival as an all-ages event and that he and Dre weren't seeing anything especially unique. It's a very real possibility, however, that the pupil caught something that eluded the teacher.

Less than a week after I moved from small-town Northern Ohio to California, I saw the World Class Wreckin' Cru perform in Sacramento, at the very start of 1985. By then, Run-DMC had become a national force, at least among young fans of Black music. The Cru was much more raw live on stage—electro beats with some speed raps from Cli-N-Tel—than what they were putting on vinyl and cassette. The night's music hardly resembled the nascent hip-hop I'd been in love with. Its constant was this outfit's DJs. Dre, DJ Yella and Lonzo were all masterful turntable technicians. Yella—whose onstage set-up sat just above me—made the biggest impression of all. I'd grown up with friends in mobile DJ crews, and Yella's skills struck me as out of this world.

But that's generally where resemblances to the music coming out of NYC ended. Take a song like "Roxanne, Roxanne," a hit for UTFO at the time. Its beats were hard, slow and rolling where the Cru songs, the ones that were not simple synth-drenched ballads, sped along at 128 beats per minute, like Soul Sonic Force's already-dated "Planet Rock." And where East Coast MCs rhymed to match a song's beat, Dre and, primarily, the Cru's main MC Cli-N-Tel rapped at half the pace. They didn't sound like anything you'd hear on the radio, and not in a good way. Doug E. Fresh's "The Show" and LL Cool J's "Rock the Bells" were monster hits in 1985, and the World Class Wreckin' Cru managed to simultaneously seem dated and immature by comparison.

By the time I caught that Wreckin' Cru show, the group was on the brink of splitting due to tensions between the group's leader and the one who in hindsight had the most unrealized potential. Mullen's email has brought me to the conclusion that this first hardcore rap show outside the South Central familiar permanently affected the producer's youthful vision.

The Lingerie festival MCs "were a lot more hip-hop cultural," Williams acknowledged. "We weren't privy to that kind of thing. The fashion, we resisted it for a while. It wasn't until the mid-80s that we embraced the B-Boy thing. We were on the cusp of R&B and funk. We had guys dressed like Prince breakdancing. We had guys in skinny ties dancing. [B-boy culture] took a long time to really hit, especially in South Central."

Williams explained that rappers at Eve's After Dark "were much more competitive, whereas at Lingerie there was a blanket of mutual respect. Nothing wrong with that. But at Eve's people were trying to make a name for themselves."

He chafed at my suggestion that Dre might have been more impressed by what went down in Club Lingerie, that crucible of Angeleno alt music, than Williams was, and that Dre's subsequent desire for a tougher, more up-to-date sound contributed to tensions within the World Class Wreckin' Cru.

"That's a fiction that people tend to write about us. Dre was always a dance head," Williams said. He pointed to early N.W.A tracks "Sumthin' 2 Dance 2" and "Panic Zone." Williams says simply that "all came out after he left the group. Dre didn't like to rehearse. That was the problem with the Wreckin' Cru."

"At one point in time we nicknamed Dre 'LL Cool Dre' because he imitated LL Cool J so much when he rapped," Williams told me. (I tried to get in touch with Dr. Dre for this joint, but dude did not call me back. He never fucking calls me back.)

Not only did the sights and sounds of in-the-flesh-Bronx MCs, DJs, b-boys, and graf artists affect Dr. Dre, in my opinion, but Club Lingerie's rock aesthetic turned his head as well. Go back to the second, insanely boisterous N.W.A album, Niggaz4life. Until Ice Cube's departure rocked the group's foundation, that record had been intended as the Eazy-E rock album. (As if "Boyz-N-tha-Hood" and Straight Outta Compton didn't have some of the hardest rap beats as yet heard in their own right.)

Take into account also N.W.A's tour with Guns N' Roses, the "California Love" video's punk apocalyptic imagery, Aftermath's forward-looking appreciation of Eminem's potential, and the Beats tycoon's eventual self-guided eight-year study of music theory and you get the portrait of an artist with an insatiable thirst for new and different sounds.

I believe that more than anything, "The South Bronx Invasion Goes West" helped Dre see beyond the kind of provincialism dictated by L.A.'s restrictive covenants, both openly expressed and subtly self-imposed. He was an ambitious boy seeing wild shit from a place he could only previously picture in his ears, and he caught two days of it in the most indie-minded of settings. People forget, but pink hair, mohawks, and visible tats, were once considered counter-cultural. Just like rap music.

Don't merely take my word on how a Brendan Mullen weekend might have opened Dr. Dre's eyes to broader horizons. Listen to Lonzo:

"We all were imitators for the most part. We saw what was selling and copied. It's like they say, 'Good artists steal.'"

If you enjoyed reading this, please login and click "Recommend" below.

This will help to share the story with others.

Follow Donnell Alexander on Twitter @donnyshell.

Follow Cuepoint: Twitter | Facebook

Source: https://medium.com/cuepoint/dr-dre-s-secret-sequined-history-95f798c3f08c